UNIVERSITY HOSPITALS OF CLEVELAND

Designing a digital and physical solution to improve wound care and enhance patient outcomes.

Project Duration

January - July 2024

Role

UX Researcher and Designer

Traditional methods of wound care instruction - such as written and verbal guidance - often fall short due to factors such as limited health literacy, physical disabilities, and a lack of clinician oversight. These challenges can lead to poor adherence to treatment plans, resulting in complications like infections and chronic non-healing wounds, especially for patients with underlying health conditions.

the problem

In this project, we worked with a clinic specializing in a unique type of skin cancer surgery. Over the course of seven months, my team and I addressed the challenges patients face when continuing wound care at home after their surgery. Our goal was to improve outcomes for patient-administered wound care by bridging the gap between clinic-based guidance and at-home treatment.

the SOLUTION

We designed a system to bridge the gap between clinic and home care. Cura, a mobile app, gives patients instant access to answers and reassurance, while a tailored instruction sheet provides clear, wound-specific guidance for easy navigation.

We jumped right in and quickly fell in love with our project. After thoroughly analyzing the project prompt, we conducted background research, which served as the foundation for our kickoff meeting.

During the kickoff, each of us was given a wound care kit and instructions, allowing us to experience firsthand the challenges patients face during home recovery. For five days, we managed our own wound dressings, giving us insights into both the physical and emotional aspects of the recovery process.

This immersive experience helped us to better empathize with our patients, and ask more informed questions moving forward. With a clearer understanding of the problem, we then identified the gaps in our research and paired them with the appropriate methodologies.

establishing a foundation

To get us started, we needed to understand our problem space, establish our research scope, and align our expectations with those of our client.

Equipped with foundational knowledge of wound care, aligned project goals, and a well-defined research plan, we then headed to Cleveland for a site visit at University Hospitals.

visiting cleveland

To get us started, we needed to understand our problem space, establish our research scope, and align our expectations with those of our client.

Our site visit to Cleveland aimed to immerse us in the clinic environment and better understand both patient and provider experiences with wound care. On the clinic side, we focused on the sequence of wound care treatment, communication between providers and patients, and any barriers or pain points in the process. On the patient side, we explored their at-home care routines, attitudes, and support systems.

During patient interviews, we spoke with seven individuals, all confident in their ability to manage wound care at home, many of whom had prior experience. They found the written instructions easy to follow, which they preferred for future reference. However, call logs revealed a disconnect—patients who appeared confident in the clinic were often calling in for reassurance soon after leaving, revealing a gap in their actual wound care proficiency.

We also conducted AEIOU observations in the waiting room to further empathize with patient experiences. Our team noticed that while patients occupied themselves with unrelated tasks like reading or using their phones, wound care instructions or support were not integrated into this waiting period.

To further understand the patient journey, we participated in a nurse mockup, where one team member assumed the role of a patient. This exercise highlighted the overwhelming amount of medical jargon and the challenge of processing post-op instructions while in a vulnerable state.

With these insights, we left Cleveland understanding the gap between patients’ perceived confidence and their actual need for ongoing support, giving us valuable context to shape our solutions.

In order to understand this we started by walking the wall. We placed our collected artifacts along the wall and silently walked along, noting questions, assumptions, needs, and opportunities. This exercise not only provided insights from our latest findings but also allowed us to revisit past discoveries, enhancing our understanding of the problem. From this exercise we took away that:

Patients call the clinic for reasons beyond wound care instructions, such as emotional support and reassurance.

The waiting time and space at the clinic have potential to be used for more opportunities, such as education, or building trust and connection.

There is a need for doctors and nurses to be more aware of the knowledge gap that exists between them and their patients.

Patients can easily experience information overload when at the clinic.

Patient Journey Map

With this, it became clear to us that we would need to make better use of different touch points throughout the patient journey to take a more human approach to the wound-care education process. So what exactly did a patient journey look like?

through a different lens

After our site visit, we synthesized and analyzed the collected information, then revisited our original project prompt. Did the information we gathered still align with our initial project direction?

Both the patient journey map and the patient archetype are models we are very familiar with and that helped us to better understand the people at the heart of our project. But there was still the component about the nurses and the doctors that we needed to look further into. Furthermore, we had learned from our site visit that there was a disconnect between the clinic’s expectations and the patient’s behavior. To better think through this we put our heads together and generated the misalignment model.

The four worlds we chose to further explore were:

Diabetes educators

Physical therapy

Mental health hotline

Children’s dentist

Patient archetype

Along with the patient journey, we aimed to delve deeper by creating patient archetypes. We wished to gain a more nuanced understanding of our target user population, including their diverse motivations and associated challenges. We generated five archetypes:

The Newcomer

The Model Patient

The No-Fuss Patient

The Determined Patient

The Disengaged Patient

misalignment model

We found that misalignment between healthcare providers' expectations and patients' behaviors may stem from gaps in health literacy and patients' post-surgical anxiety. While nurses may believe they’ve communicated instructions effectively, patients with limited health literacy or anxiety may still struggle to understand. Nurses may also not clearly convey expectations, such as consulting the wound care sheet before contacting the clinic. Additionally, patients may have difficulty expressing frustrations, leading to repeated inquiries.

Having completed the expert interviews we now wanted to dig deeper. To do this we conducted a metaphor activity that we were introduced to in our Persuasive Design class. Our goal was to understand the underlying emotions, challenges, and complexities involved in the wound-care process, from the perspective of the Doctor.

analogous worlds

As we continued to diverge in our process, we were encouraged by our mentors to explore analogous worlds, an exercise to draw parallels between at-home wound care for skin cancer patients and other domains.

We started with breaking down our domain into individual elements. Once we had those elements, we each brainstormed industries that excel in those areas. Through a voting system, we pinpointed the most analogous industries. Next, we sought overarching themes across these domains, ultimately selecting the top four for further investigation.

expanding our sights

It was now time to speak with the experts. We wanted to better understand the experience of wound care from the perspective of the nurses and doctors in our community.

expert interviews

The goal of speaking with the experts in this field was to better understand common wound care practices, as well as communication methods, patient interactions, and emerging technologies in the field.

1.

metaphor focus group

insights

1.

While some of our assumptions could be validated through desk research, others would have to be tested in-person with patients.

Unfortunately, due to unforeseen circumstances, I was unable to join my team in Cleveland but met with them and received a thorough debrief upon their return.

Synthesizing the feedback we received during testing in Cleveland we found that:

Tasks that involved added work in the clinic were a large concern for both the patients and the nurses.

Patients prefer visuals in their instruction delivery.

Patients like solutions that save them time.

value

From this activity we took away that:

When it comes to emergency situations, healthcare providers understand that patients may feel lost in a fog of uncertainty, searching for a safe harbor.

When patients call, doctors may feel that they need to be their guide through the woods.

Patient healing was compared to a balancing act as there are lots of moving parts and there could be shocking results to navigate through.

The take-home instruction process may feel straightforward to healthcare providers but can be as challenging as using a broken pencil for patients.

Metaphors, like signposts, guide patients through wound care instructions, setting expectations, and navigating uncertainties.

crazy 8s

I need my wound to heal properly and in a timely manner so that I can end the cumbersome routine.

I need to easily recall the instructions the nurse told me at the clinic to properly manage my wounds at home.

I need to have immediate answers to my questions to feel supported and reassured that my wounds are healing as expected.

I need the wound care to be tailored and customized to my specific circumstances.

To address the patient need for their wound to heal quickly we wanted to test the idea of a wound care tracker app.

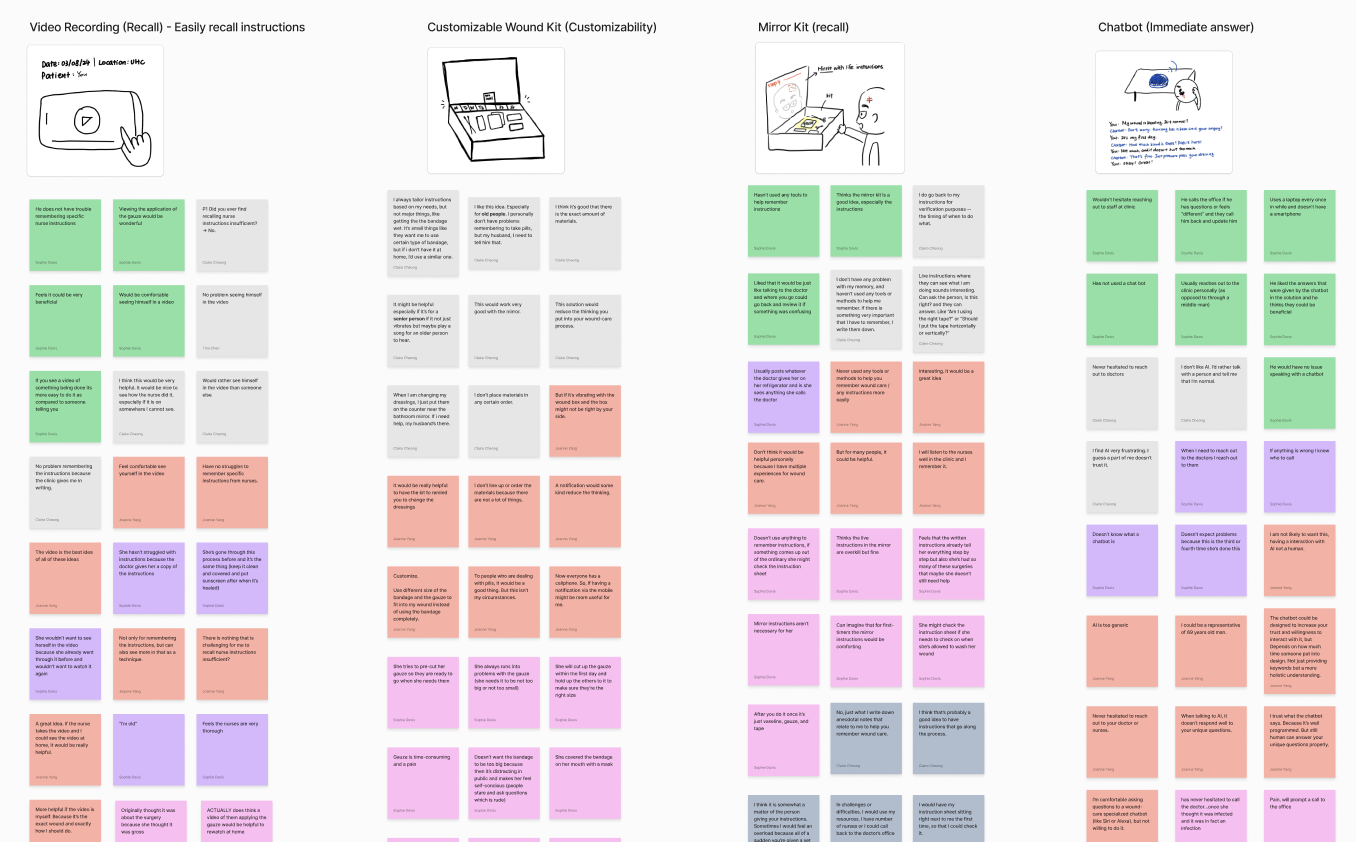

To address the patient need for easy recall of instructions we wanted to test the idea of a mobile wound care instruction app, a waiting room trivia questions, a video recording of the bandage application, and a mirror kit.

To address the patient need for immediate answers we wanted to test the idea of a digital wound care guide, and a chatbot.

To address the patient need for customization we wanted to test the idea of a customizable bandage and a customizable wound care kit.

testing

To engage patients from the UH clinic, we adapted our methodology for remote sessions. In collaboration with the clinic, we set up a room where patients could join Zoom meetings during their wait, using a QR code or phone number for easy access. Over the course of one day we guided 9 patients through our proposed solutions, listening to their thoughts and observing their reactions.

The speed dating sessions gave us valuable insights into patients’ ability to recall instructions, need for reassurance, handling of unexpected situations, and their pain points regarding their wound care experience.

Contrary to our initial assumptions, we found that:

Patients found the instructions to be easy to understand and recall. Rather, it is the unexpected situations, and the proper care of the wound that they seemed to want more information about.

Patients preferred seeking reassurance directly from healthcare professionals rather than relying on technology like chatbots or mobile apps. They placed significant trust in the doctor and the healing process.

The inefficacy of the wound care sheet caused nurses to tailor the delivery of the wound care sheet. According to one nurse, “our wound care sheet is too wordy, personally I will only go over the first page”.

According to a study we discovered during our desk research, “consumers who perceived healthcare services as personalized were more likely to consider the services as trustworthy and thus more likely to accept such services”.

After selecting our four worlds, we researched best practices from each domain. We then picked apart the key traits of these practices and brainstormed how we might be able to adapt them to our problem space.

By diving in and building models, we gained deeper insight into our project stakeholders, their pain points, and the root causes of misaligned expectations and behaviors. Our focus expanded to address multiple touch points throughout the patient journey, rather than just the final outcome. The diverse needs of our patient population also highlighted the importance of a flexible solution adaptable to various needs.

Now, it was time to get away from our desks once more and hear from the people we were working to help.

Having spoken with experts from University Hospitals and beyond, we learned:

Communication Channels: Patients typically communicate with their clinic through the electronic portal, while also using phone calls for reassurance or concerns.

Observed Patient Pain Points: Patients may struggle with assessing wounds at home, adhering to instructions, and accessing appropriate medication.

Patient Expectations: Patients are expected to reach out if they experience unexpected pain or significant changes in wound characteristics.

Instructions: Ideal at-home wound care involves patients closely following instructions.

Emerging Technology: Emerging technologies like plasma injections and stem cell therapies show promise.

Using the the user needs we had identified as a guidepost, we conducted a Crazy 8s brainstorming session to produce innovative and even unconventional ideas that would help us to assess users' reactions and comfort levels with each proposal.

storyboards

-

Initially, our storyboards were structured to have three parts: the problem, the solution, and the resolution, each featuring a narrative centered around a fictional character. However, based on feedback from pilot testing, we decided to refine the storyboards to solely focus on detailing the solution idea, allowing participants to truly envision themselves as the users of the proposed solution.

exploring patient needs

Having gained a strong understanding of the wound care process from the perspective of doctors and nurses, we were ready to delve deeper into the patient experience and explore their needs.

From our previous research we had a general sense for what our patient needs were, but we needed to hear from the patients themselves to truly understand if these were valid or not. From our understanding, the primary patient needs were:

To maximize efficiency in testing user needs, we decided to narrow our focus to the riskier ideas for patient testing.

To help guide us at this point in our process we spoke with another capstone team after our faculty informed us that this team was in a similar stage as us. While their project was very different from ours, they suggested we look into using an importance-evidence matrix to better understand what assumptions were at play, and which of those were the most critical to our progression.

The wound care procedure is not personalized beyond the clinic.

putting it all together

Having spoken with patients, clinicians, and experts, conducted thorough desk research, and visited Cleveland, it was now time to put together everything that we had learned and give our project a direction.

Our exploration into patient-administered wound care led to three key insights, offering valuable perspectives on the challenges and opportunities within our problem space and providing a solid foundation for our next steps.

5/7 nurses disclosed that they often tailor the delivery of wound-care instructions based on various patient factors including age, personality, cognitive ability, wound location, and prior experiences with wound care.

6/9 patients reported modifying their wound-care routines at home, such as trimming bandages or wearing long sleeves to bed. They are left to customize their experiences based on their own intuition and assumptions.

Although patients show high confidence for at-home wound care, they are unprepared when unexpected situations arise.

Nurses emphasized “The goal is to make the patients feel confident about understanding the wound care procedure before they leave the clinic”.

Sifting through clinic call logs, we found that 42% of calls were about complications, from concerns like wound reopening to symptoms such as itching and white spots. Some cases even escalated to ER visits.

2.

During our on-site interviews, all 9/9 patients rated their confidence in their ability to care for their wound at home as 5 out of 5.

Patients seek constant reassurance from direct conversations with trusted healthcare providers.

Our insights guided us to reframe the problem statement we were given, and re-define the problem space in a way that would more accurately guide our design efforts.

When we first received our project prompt we understood that the primary causes of failed treatment and poor surgical outcomes were:

The patient’s inability to execute treatment plans

Lack of clinician visibility into the treatment process

Inability of the clinician to intervene in a timely fashion

Encourage patients to adhere to wound-care instructions.

For two days, they spoke with fourteen patients and five nurses, and engaged in comprehensive feedback collection and iterative refinement of our seven prototypes.

Customizable instruction sheet in which the patient and the nurse work together to design the sheet.

15 out of 16 patients stated they would first call the nurses and doctors if they encountered any problems at home.

Patients rely on calls due to their trust in healthcare providers' expertise. “Usually, what they say can happen is what happens. If they tell me I can shower, I shower. Just like they told me.”

However, through our research it became clear to us that the problem behind the problem was actually:

The lack of preparedness of the patients to deal with unexpected situations

The lack of easily accessible, personalized information

We discovered through our research that when patients were faced with unexpected situations, or simply needed reassurance, their preference was to speak directly with their healthcare provider, which in turn resulted in the provider feeling overwhelmed. If we could reduce this burden on the healthcare providers, we could then enable them to dedicate more time and resources to their patients in the clinic. So the question becomes:

3.

how might we

Nurses emphasized the importance of reassurance in their interactions with patients. “It’s important to reassure the patients because people might easily forget or feel nervous.”

7/7 nurses stated that they could empathize with why patients would call but could still feel burdened having to repeat the answers that could be found on the instruction sheet.

revisiting our problem statement

1.

How might we help patients to put more trust and attention towards the wound-care materials to reduce the workload on healthcare providers?

2.

How might we ensure patients receive immediate answers and reassurance while facing unexpected situations?

Help patients to build problem-solving skills.

creative matrix

Help patients to prepare for unexpected situations.

Allow patients to effectively process wound-care information.

Reduce the anxiety of patients.

From a proactive perspective, we wanted to prepare patients for unexpected situations. We wanted increase patient adherence to instructions, thereby reducing infection rates and the volume of phone calls to the clinic. From a reactive perspective, we wanted to provide immediate support to patients when emergencies occur.

Our goal was to assist patients in navigating these problems independently, reducing their reliance on providers. By addressing this goal, we wanted to ultimately reduce anxiety and improve the overall wound care experience.

With dozens of new ideas generated from our creative sessions, we needed to establish a set of principles our prototypes would need to align with in order to bring value to both the patient and the clinic. From our insights we determined that our designs would need to:

Reduce the burden on both the patients and the healthcare providers.

guiding principles

Using three decks of cards—technology mediums, project features, and stakeholders—faculty randomly drew cards from each deck and formed scenarios. Each was discussed for five minutes using the Yes...and method, promoting idea generation and exploration.

ideation and structuring

With these how might we questions guiding our design process, it was time to begin ideating and really taking a look at what we wanted our solutions to accomplish.

The goal of the creative matrix was to foster divergent thinking, avoid fixation, and open our process to others.

One method that helped us broaden our design thinking was prompt-inspired idea generation. In this activity, we used prompts to spark as many related design ideas as possible within a set time limit. For example, we had three minutes to brainstorm ideas based on the prompt, beyond fingertips touching pictures under glass.

prompt-inspired idea generation

At a high level, we were working to create value for both patients and providers. We wanted to reduce patients' reliance on providers by building their confidence and ability to handle unexpected issues. As we looked at our newly generated ideas and guiding principles, we came to understand that there were two types of solutions at play: proactive and reactive.

categorizing information

mid-fidelity design

To conduct this exercise we would need to sort our assumptions by how important they were, and how much relevant evidence we already had to support them. Then, we would focus on testing whichever assumptions we had the least evidence on, but deemed the most important.

Sends follow-up notifications

of participants found the notification to be highly useful for their wound care process.

Cura provides patients with immediate answers

Instant access

Average callback time for call is currently 2 hours.

Offers patients solutions

Help at any hour

“I'm generally comfortable with calling, but if it's late at night I hesitate" - Patient

In addition to the Cura app, we designed an instruction sheet for patients to take home. This redesigned instruction sheet organizes information to improve navigability, incorporates illustrations and color for visual learners, and highlights dos and don’ts for specific wound locations.

Filters calls to the clinic

After developing and testing our final high-fidelity design with patients, we identified the following key benefits of our solution:

testing

At this point, each of our ideas still had several assumptions backing them. So what did we have left to learn about each of our ideas, and how were we going to learn that information?

riskiest assumptions

testing

By combining direct user engagement with rapid iteration, we were able to make informed adjustments and validate our concepts effectively. This rigorous testing process provided us with valuable insights, guiding us as we moved forward in developing solutions that truly met the needs of our users.

Building on the proactive and reactive framework we had established, along with the insights gathered from our site visit to Cleveland, we zeroed-in on two primary ideas. We wanted to:

Revamp the existing four- page instruction sheet.

Design an all-encompassing patient-facing app to assist patients in their at-home wound care.

To refine the call feature, we tested an audio-only version against one with on-screen visuals. Participants preferred the latter, as the visuals helped them provide clearer, more specific information, enabling the AI to respond more effectively.

Smart bandage in which the bandage does all the work for the patient.

testing results

Image-based card in which the patient is sent home with index cards with instructions specific to their wound.

Voice GPT in which the patient can ask questions and receive immediate answers.

Wound care hub in which the patient has access to all of the materials they need to change their dressing.

Smart mirror in which the mirror walks the patient through how to change their dressing.

Nurse update in which patient images are sent to the nurse.

cura

Months of research led us to design the reactive component of our system of solutions, Cura—an app designed to provide immediate assistance to patients at home.

Using insights from our previous testing session, we refined our design and tested it with 13 additional participants from both Cleveland and a local senior center.

Initially, our app included both a messaging assistant and a voice assistance to gauge user preferences. Only 3 out of 13 participants favored the messaging assistant, with many struggling to type their questions. Some even tried speaking to the messaging assistant, highlighting a preference for verbal communication. Based on this, we removed the messaging feature and focused on the more intuitive call feature.

We also compared the use of real images versus illustrations. While participants felt uncomfortable with real images showing blood or infections, they found illustrations more approachable and easier to understand, facilitating more comfortable communication with the AI.

mid-fidelity 2.0

final design

Independent problem-solving

“I am more of an introverted person so I’d prefer to look things up myself” - Patient

4.

Cura cuts down on clinical workload

Collapsible Box

3.

Cura fits the mental model of patients

Uses the doctor’s voice

“Dr. Carroll’s voice sounds very reassuring to me” - Patient

Resembles an actual call experience

The primary method of communication between patients and the clinic is currently through phone calls.

Wound-specific information

Daily dos and don’ts

Personalized onboarding

instruction sheet

2.

Cura is personalized to patients

83%

60%

of participants were comfortable inputting wound-related personal information into the app.

100%

of participants found the app to be highly helpful in providing personalized assistance.

motivation

format exploration

Digital Co-Design

value

Although comprehensive, the clinic’s instruction sheet had room for improvement: it was not fully personalized, tended to be repetitive and lengthy, and was challenging to navigate. Our goal was to enhance the clarity of information to encourage patients to refer back to it more frequently during their at-home wound care journey.

As we navigated our design process, we explored various formats for the instruction sheet. Rather than limiting ourselves to a paper format, we tested different options with patients to better understand their needs.

"The box might be too big to store in my bathroom” - Patient

"A box could be cumbersome to carry” - Patient

Deck of Cards

final design

After testing various formats, we returned to an improved paper version of the instruction sheet. We found that patients were familiar with it, and found it easier to navigate. We also found that this format minimized the burden on nurses, who can simply print and then distribute the appropriate version based on the patient’s wound location.

"Good info, but I find it easier to just see it together in one sheet.” - Patient

"I like the sheet of paper more than the cards because it’s all in one place and I don’t have to flip through and get messy” - Patient

“I would rather just have it handed to me” - Patient

“This will add a lot of time. I have to bandage them and then dress them. This will add 2-5 minutes for every patient” - Nurse

Supporting visuals for enhanced clarity

Images included to improve patient understanding and make information easier to follow.

Streamlined information layout

Content is reorganized and grouped for easier access and better usability.

After developing our final high-fidelity design, we tested both the original instruction sheet and the redesign with participants. We compared the time-on-task and the participants' ability to accurately find information. Our findings were as follows:

9.6

average number of seconds saved by participants navigating the redesigned instruction sheet as compared to the original.

4.75

Clear information hierarchy through design

Applied color, typography, and grid structure to establish a clear and intuitive information hierarchy.

average perceived helpfulness of the redesigned instruction sheet on a scale of 1 to 5.

80%

percentage of participants who preferred the redesigned instruction sheet over the original.

conclusion

We were tasked with enhancing outcomes for patient-administered wound care by bridging the gap between clinic and home care settings. Over the course of seven months, we worked diligently to design a system of solutions that accomplished just that.

To improve preparation for both patients and nurses at the clinic, we redesigned the instruction sheet that patients are sent home with. To provide reassurance and immediate answers once they’re at home, we developed the Cura app.

Our goal was to alleviate the burden on both patients and clinic staff by empowering patients with the tools to handle unexpected situations, build problem-solving skills, and adhere to care instructions. In doing so, we aimed to enhance patient confidence and reduce anxiety.

.

Location-specific care instructions

Provides targeted and practical guidance tailored to each patient’s unique wound location.